West Coast Sea Glass

Genuine Sea Glass Jewelry and Bulk Sea Glass

New York Times "From Junk to Collectible, Shaped by Time and Tide"

New York Times "From Junk to Collectible,

Shaped by Time and Tide"

New York Times "From Junk to Collectible, Shaped by Time and Tide"

October 17, 2010 -

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/19/science/19glass.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

HYANNIS, Mass. — Laura McHenry started walking Cape Cod beaches searching for sea glass a few years ago, when her marriage was breaking up and she was looking for something she and her daughter Katie, could do together for fun. “Sometimes we’ll just sit on the rocks and just comb through,” said Ms. McHenry, who lives in Centerville, Mass., as Katie, 10, displayed her finds nearby. “It’s a great place to talk.”

History draws Rachel Mack, of Grandview-on-Hudson, N.Y. “These could have come from the Half Moon” she said, pointing to white clay pipe stems, each an inch or two long and perhaps half an inch in diameter. She finds these artifacts when she kayaks along the shore of the river Henry Hudson sailed 400 years ago.

Richard LaMotte’s wife got him into it. She is a jeweler who works with sea glass, and he went with her on expeditions to Chesapeake Bay beaches near their home in Chestertown, Md. Mr. LaMotte, who works for a water analysis equipment company, got interested in how water acidity affected the glass, and how the chemicals used to make glass changed its color over the decades. Soon he was consulting archaeologists and studying the history of American glass manufacturing. Now his book, “Pure Sea Glass” (Sea Glass Publishing, 2004), is a bible for collectors.

They and hundreds of other enthusiasts gathered here this month for the annual meeting of the North American Sea Glass Association, to celebrate a hobby that seems an odd mix of amateur archaeology, environmental monitoring and antique collecting, with a little chemistry thrown in.

At the meeting they trade shards of glass and porcelain, buy and sell sea glass jewelry and crafts, seek expert help identifying their finds and hear presentations on shipwrecks, the glass industry and other topics.

Membership is growing and enthusiastic,

Mary Beth Beuke of Sequim, Wash., the group’s president, said in an interview that sales of sea glass and its crafts are booming, even though the glass itself “is getting harder to find.”

Though sea glass collectors talk about bottles, porcelain and other cargo lost in shipwrecks, most sea glass originated far more prosaically, in garbage dumped into the ocean or piled in coastal landfills. A blue shard may be the remains of a Noxzema jar or a bottle of Bromo-Seltzer; old Coke and beer bottles produce pale-green and dark-brown shards. Now this kind of dumping is mostly a thing of the past; bottles are made of thinner glass, and plastic has replaced glass in many products.

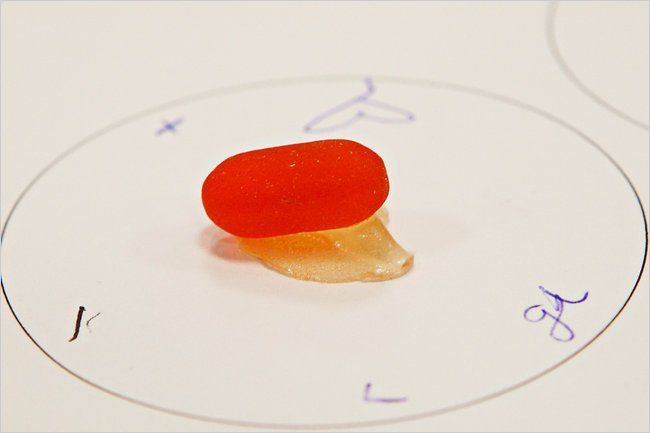

Still, collectors and volunteers at the meeting say there is plenty to find if you know where and when to look, and what to look for. According to Mr. LaMotte, orange shards often come from glass items manufactured in the Art Deco period or from tableware manufactured in the early 1900s. Red shards are rare — old Schlitz beer bottles are one source. Some yellow shards are from glass made with uranium dioxide. These shards glow when exposed to an ultraviolet or “black” light.

But sea glass hunters do not necessarily limit themselves to glass. Some look for crockery shards, bottle stoppers, fragments of old toys, marbles — virtually anything that left human hands to be tumbled by the sea.

Devoted collectors find themselves studying glass in antique shops, at shows for bottle collectors and in museums. Eventually, some become adept at identifying even tiny finds.

At her display, Ms. Mack picked up something that looked like a dark gray stone. Small chips revealed its shiny black interior — “glass from the 1700s,” she said. “It probably held beer.”

The meeting also offered plenty of advice on finding good hunting spots. Seek out shorelines where there was manufacturing or shipping at least 50 or 100 years ago, accomplished collectors advise. For example, Ms. Mack said she has good hunting at the sites of former cross-Hudson ferry routes, where she finds the remains of bottles thrown overboard a century or more ago.

Sites with prevalent onshore winds are best, Mr. LaMotte advises in his book, and the best time to look is the first low tide after a big storm.

“It’s frustrating, but it’s fun,” said Vickie Carter of Newark, Del., a volunteer at the meeting. She collected sea glass as a child in Montauk, on Long Island, but when she took her husband there more recently, the pickings were slim. Today they hunt Woodland Beach, Del., in search of what she calls “the perfect piece — the perfect blue, the perfect red, the perfect orange.”

A perfect piece, she said, is smooth and totally frosted. When they find one, she said, “it goes into a jar and we continue to look.”

Carole Lambert, whose “Sea Glass Hunter’s Handbook” is her third on the subject, confesses that her interest feels, at times, “a bit loopy — picking up garbage from the beach.”

Ms. Lambert, a writer and editor who now lives in Islesboro, Me., searched for years in Rockport, Mass., where she accumulated large quantities of tiny porcelain body parts — arms, legs, noses, faces, “an ear as big as my thumb.” Eventually, she said, she learned they were the remains of tiny dolls given away in the 19th century with purchases of flour and other staples.

Why were there so many? Ms. Lambert found the answer at the

Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., in the form of a bill of lading from a ship that foundered, spilling crates of tiny dolls.

As sea glass grows harder to find, people who want to work with it are creating their own, tumbling pieces of glass in sand-filled machines or treating them with muriatic acid or other corrosive substances.

“That’s one of the reasons we started the association,” Ms. Beuke said. “We started running into people who say ‘sea glass’ and they mean something that is artificially conditioned.” The real thing, she said, “has been conditioned only by the ocean and its elements. It has been on a journey and has a history to it.”

Mr. LaMotte, whose book display was thronged by collectors, said many had asked him to identify shards he could tell “immediately” were not the real thing. “You get this very satiny sheen, almost like a filmy sheen,” he said.

On the other hand, occasionally a collector will hit a shoreline jackpot. One is Jean Hood of Buffalo, who brought a small satchel filled with shards she had found on the shore of Lake Erie and hoped Ms. Lambert could identify. The two puzzled over a piece of red glass, roughly two inches square, with a grid of regular bumps — a lens from a boat’s running light, Ms. Lambert concluded.

As they chatted, Ms. Hood remarked that she sorts her finds by color, “all the reds, all the oranges.”

“All the oranges?” A jeweler from a nearby booth pricked up her ears.

“The rarest color,” Ms. Lambert murmured. Pieces of orange sea glass can sell for hundreds of dollars.

If the association is firm against manufacturing sea glass, there is less agreement on “seeding” beaches with glass. Though some collectors already engage in the practice, Mr. LaMotte sees obvious safety and environmental problems with putting broken glass on the beach. Anyway, Ms. Lambert said, it might take 50 or 100 years for a piece of broken glass seeded on a beach to achieve the patina of sea glass. “Until then, it’s just trash.”

By Cornelia Dean.

A version of this article appeared in print on October 19, 2010, on page D4 of the New York edition.